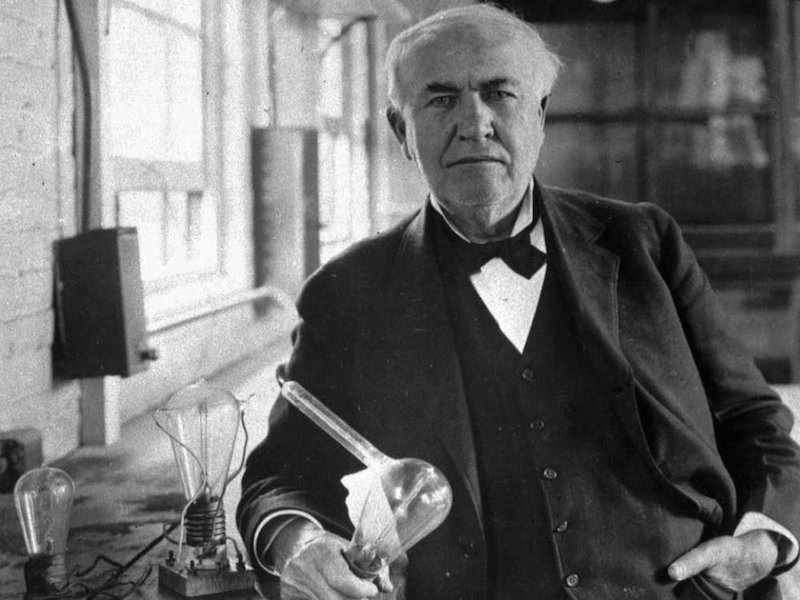

Thomas Edison, whose 169th birthday falls on Feb. 11, is best known for inventing the lightbulb and for being one of the fathers of movie-making and sound recording, but there's a less-recognized invention the Wizard of Menlo Park designed that in many ways could have changed the course of American history - that is, if it had ever been given a chance. With the current 2016 presidential primaries underway, Edison's first patented machine - and one of his biggest flops - is well worth examining.

At the age of 22, the man that would go on to have 1,093 patents to his name during his lifetime was a lowly telegraph operator who had recently been fired from his job at Western Union for tinkering with a lead-acid battery (which leaked sulfuric acid onto the floor, irreparably damaging it) on the job. The event propelled Edison to work on what would become his first patented invention: a machine which recorded the ballots of would-be voters with the help of a simple switch and an electric current.

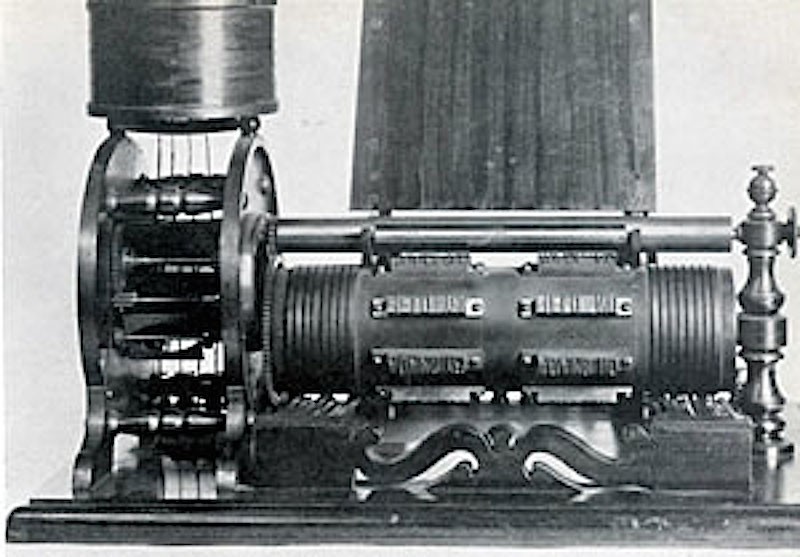

At the time, laying claim to the first patent for a voting machine was a pretty hot ticket: according to Rutgers University, governmental bodies like the New York state Legislature and Washington, D.C.'s city council were considering the utility of a mechanical recorder in lieu of roll calling votes - i.e., actually having reps say "aye" or "nay" one by one, with a scribe tallying up the votes by hand. Edison's plan was to speed up the process with a machine, which he named the "electrographic vote-recorder," that could let legislators vote with the flip of a switch - one end would signifiy a "yes" vote, and the other a "no" vote - and deliver the information via electric current to a main recorder, which would dispense the votes into two columns. After the legislators voted, a clerk would feed a piece of chemically-treated paper, which would then be used to "print" the votes out for everyone to see.

Edison beat his competitors to the punch - or at least the patent office - and was issued an official U. S. copyright on his device, numbered 90,646, on June 1, 1869.

Unfortunately, the machine might have been a bit too ahead of its time. After a fellow telegrapher named Dewitt Roberts purchased an interest on the patent for the sum of $100 (around $1,754.39 with today's inflation), Edison's colleague took it to the nation's capital, showcasing it to members of Congress in Washington, D.C. to display its viability. The response? The chairman of the committee responsible for rubber-stamping the machine for government use (or adversely chucking it) scoffed, "if there is any invention on earth that we don't want down here, that is it."

The U.S. legislative bodies stuck to roll-call voting for the next 10 odd years or so, which was more often a disservice to constituents than not; as a Rutgers University page dedicated to Edison's first patented invention pointed out, the manual roll call method "enabled members [of government bodies] to filibuster legislation or convince others to change their votes." It wasn't until 1881 until the patent for the first official voting machine, invented by Anthony Beranek, was approved for use in an American general election -- and in the end, Edison's design remained unused, collecting dust in the patent office. (Despite the advent of electricity and everything involving computers, the Senate still uses the roll call method to this day.)

Then again, as the gumption-powered Edison once said, "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work." So despite the fact that Edison's first patent failed to make its mark on the American landscape, if his later inventions are any indication, the saying stuck.

Source: How Stuff Works, Rutgers