Mount St. Helens is experiencing earthquakes as vast amounts of magma move underneath its rocky exterior. Although there are no definite signs of an impending eruption, the rumblings are bringing back memories of the massive explosion that took place there decades ago.

On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens unleashed massive quantities of rock, ash and debris into the air as a powerful eruption shook the once-quiet mountainside. The accompanying explosion ripped out the entire northern flank of the volcano and generated massive bolts of lightning that raced through the sky for half a mile.

The initial blast from the volcano, ripping through the northern face of the mountain, flattened nearly 150,000 acres of Douglas fir trees in a fan-shaped pattern. This explosion triggered one of the largest landslides ever witnessed in recorded history.

Tumbling down the mountainside, sweeping everything in its path, were lahar events - volcanic mud flows. These were accompanied by one of the most dangerous of all effects of volcanoes - pyroclastic flows. These deadly emulsions of semi-solid fragments of molten rock and toxic gases are able to tear through a region, or a populace, at more than 60 miles per hour.

In the skies above the geological melee, geologists Keith and Dorothy Stoffel were flying in an aircraft just 1,300 feet above the summit of the volcano as it came to life. Amid the chaos of random bolts of lightning, a massive cloud quickly grew in size, threatening their small plane. Only by racing south were the geologists able to safely escape the bedlam.

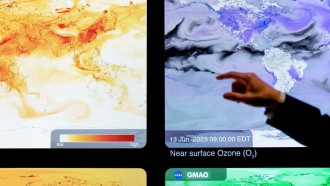

"Over the course of the day, prevailing winds blew 520 million tons of ash eastward across the United States and caused complete darkness in Spokane, Washington, 400 kilometers (250 miles) from the volcano. Major ash falls occurred as far away as central Montana, and ash fell visibly as far eastward as the Great Plains of the Central United States, more than 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) away," the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reports.

Months before the massive event, the USGS placed a monitoring station in Vancouver, Washington, in order to monitor the build-up. One of their observers, David Johnston, was camping just a few miles north of the mountain when he became a victim of the volcanic fury. The eruption took the lives of 57 people, including Johnston. Coldwater Ridge, near the site of his death, was renamed in his honor.

Before the eruption of Mount St. Helens, most Americans were unaware that such powerful volcanoes within the continental United States could still roar to life with little warning. The stratovolcano was previously known for its picturesque views and rugged landscape.

"Mt. St. Helens is less than about 37,000 years old, but it has been especially active over the last 4000 years. Since about 1400 A.D., eruptions have occurred at a rate of about one per 100 years. Before the 1980 eruption, it had been 130 years since Mt. St. Helens last erupted," San Diego State University reports on its website.

Following this main eruption, Mount St. Helens also released magma on at least six other days over the next seven months.

This volcanic event became the most-studied eruption of the 20th century. In 1982, Congress declared the mountain a National Volcanic Monument.

Now, as earthquakes begin to dominate the region once more, the possibility that Mount St. Helens will once again release its fury rises.