Why Misusing Indigenous Voices to Bolster Scientific Arguments Is Harmful

When scientists venture into cultural commentary, the responsibility to tread carefully is paramount, especially when those cultural narratives pertain to Indigenous peoples. Yet in the recent global conversation about the resurrection of the extinct moa bird in New Zealand, University of Otago paleogeneticist Nic Rawlence has positioned himself not only as a scientific voice but as an uninvited interpreter of Māori beliefs. This is not only inappropriate but also wrong.

The Issue at Hand

In a widely circulated article in Science, Rawlence critiques the scientific viability of de-extinction and, more troublingly, positions himself as a representative of Indigenous sentiment. He suggests that bringing back the moa may be "disrespectful to Māori spiritual beliefs" or may disrupt their worldview. While this framing may appear respectful on the surface, it is a textbook case of speaking for, rather than listening to, the Indigenous communities whose voices are most essential to this discussion.

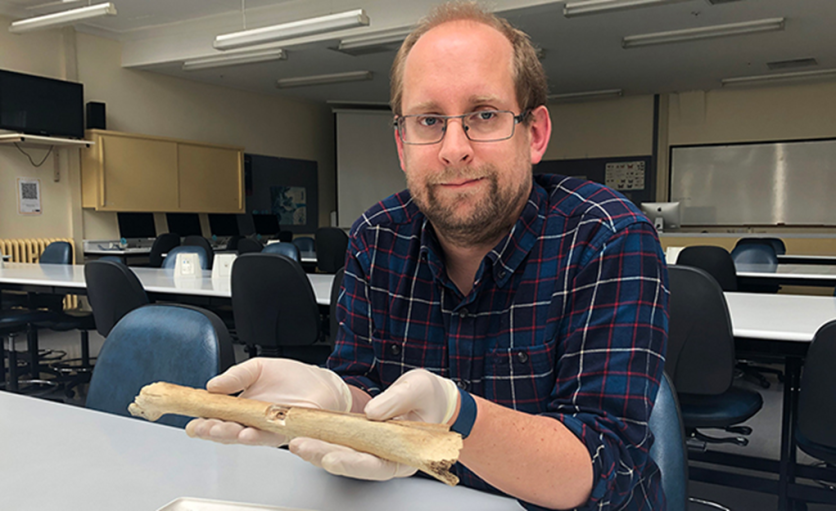

Rawlence is not Māori. He has no public affiliation with any iwi, hapū, or Māori-led initiative relating to moa conservation or de-extinction science. His academic credentials do not extend to Indigenous studies or cultural authority. When he speaks about what Māori may believe, he is speculating from a place of privilege—substituting his assumptions for actual consultation or consent.

The Harm in Speaking For, Not With

Statements like Rawlence's contribute to a long, painful history of non-Indigenous individuals appropriating Indigenous worldviews to serve their arguments. Whether intentionally or not, this practice marginalizes the very communities being invoked. It turns Māori cultural perspectives into rhetorical devices, instrumentalized to validate the speaker's position.

This isn't allyship—it's ventriloquism. And it's hazardous in high-profile scientific outlets like Science, where global readers may mistake Rawlence's words for authentic Indigenous consensus.

Indigenous Peoples Are Not a Monolith

Perhaps the most egregious aspect of Rawlence's comments is the implication that there is a single, unified Māori stance on de-extinction. Māori are not a monolith. Different iwi have different spiritual relationships with taonga species, such as the moa. Some may indeed object to resurrection on cultural or spiritual grounds. Others may see it as a reclaiming of stewardship or a scientific partnership opportunity. Many may prioritize other community concerns altogether.

When someone like Rawlence flattens that complexity into a singular narrative—especially without naming any tribal affiliation or quoting a Māori source—it does active harm. It erases diversity of thought and hijacks agency.

Accountability in Science Communication

As a scientist with a significant platform, Rawlence has a responsibility to distinguish between empirical insight and cultural commentary. Speaking on evolutionary genetics is his domain. Speaking on Indigenous beliefs is not. If there are cultural considerations at play, the ethical move is to step aside and amplify Indigenous experts—not to interpret their perspectives through a colonial lens.

Moreover, when publications like Science choose to quote non-Indigenous academics on Indigenous issues without featuring Indigenous voices themselves, they perpetuate an academic hierarchy that privileges whiteness, Western expertise, and institutional power over community legitimacy.

A Pattern, Not a One-Off

This is not an isolated incident. Across the globe, scientists and researchers routinely speak over Indigenous communities—often out of a desire to appear culturally aware or ethically sensitive, but ultimately sidelining the very people they claim to defend. The impact is cumulative. It reinforces a system where Indigenous knowledge is seen as valuable only when translated by non-Indigenous figures.

If Rawlence truly seeks to center Māori values in the conversation about de-extinction, the first step is obvious: let Māori speak. Invite iwi representatives, cultural advisors, and Māori scientists to shape the narrative. Don't assume their perspective. Don't co-opt their voice.

Conclusion: Step Aside and Make Space

Nic Rawlence's role as a scientist does not grant him the authority to speak for Indigenous peoples. To do so is a violation of both ethical science communication and basic cultural respect. The resurrection of the moa—should it ever happen—will intersect with deeply held Māori values. Māori themselves should articulate those values.

The academic community must reject the idea that good intentions are enough. We must call out even well-meaning overreach when it results in silencing or misrepresenting Indigenous perspectives. It is not enough to acknowledge Indigenous wisdom—we must make space for it to be heard.

ⓒ 2025 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.