A violinist with 2.3 million TikTok followers performs a dazzling 15-second arrangement of Paganini's Caprice No. 24, earning thousands of likes and comments praising their "incredible talent." Yet ask that same performer about Fritz Kreisler or Jacques Thibaud (legendary violinists who defined the instrument's golden age) and you'll likely be met with blank stares.

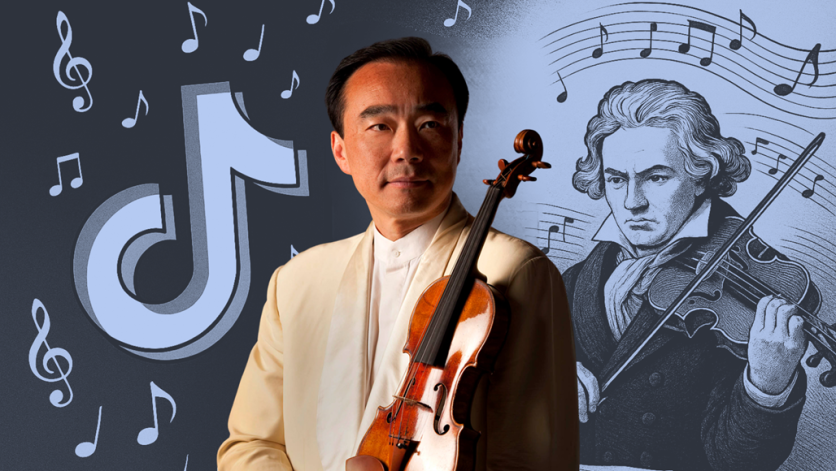

This disconnect between viral fame and musical foundation reflects classical music's deepest identity crisis in generations. While 2.6 million posts featuring Chopin populate TikTok, and conservatory students arrive technically proficient yet unable to focus for an hour without checking their phones, Grammy-nominated violinist Cho-Liang Lin watches a troubling erosion of the very principles that built classical music's greatest traditions. Major orchestras chase viral moments with memes and backstage antics, prioritizing Instagram engagement over the patient craft of musical mastery.

Cho-Liang Lin's decades-long career (from his groundbreaking performances with the Philadelphia Orchestra to his 18-year leadership of La Jolla SummerFest) offers a stark counterpoint to today's instant-gratification culture, revealing how social media's dominance threatens to strip classical music of its soul.

Cho-Liang Lin on the Erosion of Traditional Practice

Walk into a practice room in 1975: no buzzing phone, no notification pings. Just a musician, an instrument, and hours of uninterrupted focus. "When I was their age, there was nothing to distract me. There was no phone, no cell phone, not even email or fax," recalls Cho-Liang Lin, who teaches at Houston, Texas's Rice University's Shepherd School of Music. "Once I walk into a practice room, I do nothing except practice."

Today's reality looks different. Students strive to practice while facing constant digital interruptions. The teaching methods developed by legendary pedagogues like Dorothy DeLay at Juilliard require something that now seems almost quaint: sustained attention. "I listened to my students play, I watched them, and I try to figure out how to get them to analyze their own plane so that each component in the violin can be set apart from each other," Cho-Liang Lin explains, addressing concerns about student burnout in the modern academic environment.

TikTok doesn't just reward quick content; it fundamentally reshapes what musicians think success looks like. Students now "utilize internet platforms to gain fame" through "short two-minute videos playing a quartet version of a Beatles hit song." The verdict from traditionalists? "People want you, they think that it's really, really good."

The numbers tell a seductive story. One night at the Met reaches 3,800 people, tops. One Instagram post? That could hit hundreds of thousands, even millions. But experienced musicians aren't buying what social media is selling.

"If you do quality practicing for one hour, that's better than two hours of wandering around, like texting somebody three minutes and then practice another five minutes and then back to texting three minutes," Cho-Liang Lin observes. "That's pretty useless."

What observers are seeing isn't just distracted practice but a complete reimagining of how people consume classical music. Those viral clips turn centuries-old masterpieces into background music for studying, mood enhancement, or aesthetic vibes. Beethoven becomes a productivity hack. Chopin gets reduced to a sleep aid.

Historical Amnesia in Classical Music

Fritz Kreisler and Jacques Thibaud were towering figures in violin history, "lionized in their time." Today's students? They're more likely to know a TikTok violinist with 500K followers than these foundational artists.

"Young musicians start to forget," the observation goes. "A lot of young conservatory students, even advanced students, they're not aware of the tradition of playing."

This isn't just generational grumbling. Understanding where an art form originates influences how musicians interpret it. Consider the visual arts comparison: "If you want to be a painter, for instance, it would be really nice for you to learn something about the Flemish School, the Renaissance School." Artists need to know their roots to grow.

Consider the trendy Dark Academia and Cottagecore movements on TikTok. Sure, they introduce classical music to new audiences, but at what cost? A Chopin nocturne becomes detached from its context, no longer reflecting 19th-century Romanticism or Polish nationalism, but merely another soundtrack for an aesthetic mood board.

Traditional musical education tells a different story. When Isaac Stern mentored young musicians, the lessons went further than bow technique. "He taught me how to play with other people, how to order good dinner," Cho-Liang Lin remembers from his time with the master. Being a musician meant being a complete artist, someone who understood culture, history, and yes, even fine dining. It was about becoming a well-rounded human being, not just a content creator.

Metrics versus Mastery

The uncomfortable truth: what makes musicians successful on social media has almost nothing to do with what makes them great musicians. "What really counts is your quality of playing, your integrity as a musician and your ultimate skill as a violist," traditionalists insist. But scroll through any classical music hashtag, and a different story plays out.

Baritone Lucas Meachem laid it bare in his blog about social media strategy: maintaining an online presence requires constant collaboration and content creation. Every hour spent crafting the perfect Instagram reel is an hour not spent in the practice room. It's a zero-sum game.

Even the big institutions are getting swept up in the chase for clicks. The Los Angeles Philharmonic serves up classical-themed memes. The Boston Symphony Orchestra chops their performances into bite-sized social media snacks. These aren't just marketing decisions; they're reshaping how people think about classical music itself, a trend that has significant economic implications for musicians in the streaming era.

"Technology democratizes education, but it's still crucial to maintain the personal connection that music thrives on," some acknowledge. Fair point. But can musicians really learn the subtleties of phrasing, the architecture of a sonata, or the emotional depth of a Brahms symphony in 15-second increments? Many experienced teachers remain skeptical, pointing to students who arrive technically solid but missing something deeper.

Balancing Technology and Tradition

The goal isn't advocating for a return to the Stone Age. "Technology should enhance rather than replace musical fundamentals," goes the thinking. A slow-motion video analyzing bow technique? Useful. Turning an entire musical identity into TikTok content? That's where problems start.

The advice to students attempts to strike a balance that most struggle to find. Sure, build that online presence if desired, but remember what really matters. "Regardless what your career path, I hope you learn how to work with other people. You are in an orchestra and you have to play well in order to support others, but you're not always the star."

That collaborative spirit? It's the antithesis of social media's main-character syndrome. TikTok rewards the flashy soloist who can grab eyeballs in seconds. Classical music has always been about something different: holding an audience's attention through a 40-minute symphony, working as part of an ensemble, serving the composer's vision rather than a personal brand.

Traditional career paths still produce results. Cho-Liang Lin's 18-year tenure as Music Director of La Jolla SummerFest saw him commission 54 new works. His Grammy nominations and continued relevance as performer and educator came from decades of disciplined practice and deep musical understanding, not viral moments. Festival appearances at prestigious venues like the Orchestra of the Illinois Chamber Music Festival showcase the enduring value of this traditional approach. This commitment to artistic excellence continues with his upcoming performances of Tan Dun's Hero Concerto and chamber music appearances.

What does the future hold? The prescription is clear, if difficult: young musicians need to resist the easy dopamine hits of digital fame in favor of the harder path to genuine mastery. "The moment you think you know everything, you stop growing." Real musical development demands something social media actively discourages: patience, humility, and the ability to delay gratification.

The perspective cuts through the noise of the digital age with refreshing clarity. Social media can be a useful promotional tool. But when it comes to preserving what makes classical music special (its depth, complexity, and connection to centuries of human artistic achievement), no amount of likes, shares, or viral videos can substitute for the fundamentals. As Cho-Liang Lin demonstrates through his career and teaching, the task facing today's young musicians isn't just learning to play their instruments; it's learning to resist the siren song of instant digital validation long enough to develop something worth sharing.

ⓒ 2026 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.