On an October afternoon in 2003, in the city of Nasiriyah, Iraq, nine-year-old Saleh Khalaf was walking home from school when something metallic caught his eye. The small object, half-buried in the dirt, looked like a toy. It was not.

When he picked it up, the unexploded cluster bomb detonated. The explosion killed his brother, Dia, instantly. Saleh's body was torn apart. His left arm was severed below the elbow. His left eye was destroyed. His abdomen was perforated by shrapnel, and a fragment lodged deep within his brain.

His father, Raheem, rushed him to Saddam Hussein Hospital in Nasiriyah, where doctors worked desperately with limited supplies. Within days, infection and gangrene spread. Knowing his son was dying, Raheem bribed his way through checkpoints to reach Tallil Air Base, a U.S. military installation nearby. What waited for him there was not only a trauma team but a surgeon who would defy protocol to save a life.

The Moment That Changed Everything

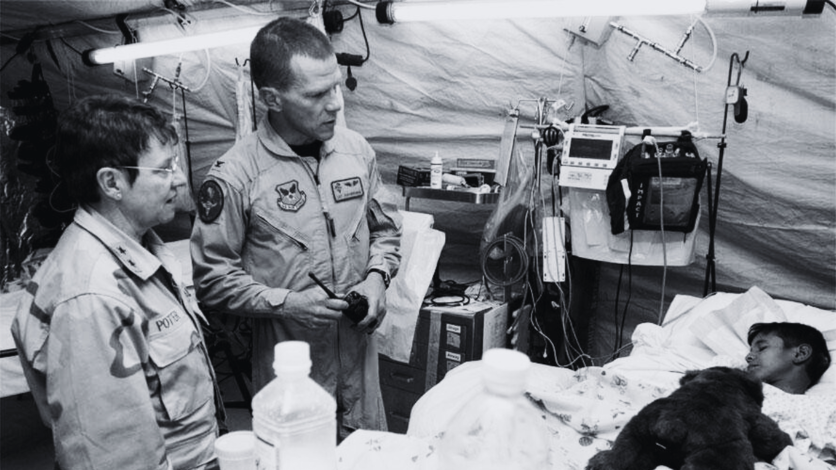

At Tallil Air Base, Lt. Col. Jay Johannigman, a trauma and critical care surgeon with the 332nd Expeditionary Medical Group, had been treating American and coalition troops for months. His orders were clear: civilians could not be treated unless cleared through higher command.

Then the Iraqi boy arrived. The boy was barely conscious, septic, and moments away from cardiac arrest.

Military rules said no. Humanity said yes.

Johannigman ignored the restriction. He performed emergency surgery to clean the wounds and close the abdomen. The child's chances were near zero, but the team refused to give up. After multiple operations, the boy's vital signs stabilized.

When he opened his eyes days later, Johannigman brought him water. Saleh whispered, "Thank you." The surgeon saw something extraordinary in his calm persistence, something almost unshakable.

He began calling the boy "Lion Heart."

The name would follow him for life.

Operation Lion Heart

Even after stabilization, it was clear that Iraq's limited medical infrastructure could not sustain Saleh's recovery. Johannigman began pushing for an air evacuation, something nearly unheard of for local civilians at the time. Through coordination across military and humanitarian channels, Saleh was transferred first to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany and then to Children's Hospital Oakland in California.

On November 8, 2003, Saleh arrived in the United States, accompanied by his father. Other hospitals had declined to take him, citing liability and logistics. Oakland said yes.

There, under Dr. James Betts, the hospital's chief of surgery, Saleh underwent more than a dozen operations to repair his abdomen, remove embedded shrapnel, and reconstruct facial and ocular injuries. During one surgery, doctors removed a small metal fragment that had lodged in Saleh's brain since the explosion.

By December 23, the boy who had arrived near death was walking down the hallway unassisted.

When Dr. Johannigman made a surprise visit that winter, the boy spotted him, stood up, and walked into his arms. "He saved my life," Saleh said softly to reporters later. The hospital staff wept.

The San Francisco Chronicle began documenting the story under the title "Operation Lion Heart." Written by Meredith May and photographed by Deanne Fitzmaurice, the series captured the moral complexity and fragile humanity of wartime medicine. Fitzmaurice's images of the boy, frail but smiling with one eye bandaged and a prosthetic arm gleaming under fluorescent light, became symbols of survival amid destruction.

The Boy Who Would Not Break

Saleh's recovery defied all expectations. Though initially mute from trauma, he began to communicate through drawings, then picked up English quickly. His body grew stronger, and his sense of humor returned. Nurses called him "the miracle kid."

Upon receiving asylum in the United States, Saleh and his father embarked on a fresh journey in Oakland. Saleh enrolled in school and tried every sport he could, even soccer, despite his prosthetic arm. His mother, Hadia, and siblings remained in Iraq during the height of the conflict, only reuniting years later after the violence subsided.

By 2006, Saleh was thriving in California. He towered over his classmates, eager to learn, with the same grin that had captivated the medical staff in Iraq.

In 2015, he graduated from Oakland International High School, standing six feet tall and full of plans for the future. "I want to help people the way they helped me," he told local journalists at the time.

The bond between the boy and the doctor remained strong. Saleh continued to refer to Johannigman as "Dr. Jay." Whenever asked what kept him going, he pointed to the surgeon who had refused to walk away.

Today

Two decades later, the story still resonates. In 2024, photographer Deanne Fitzmaurice revisited Saleh's life for her new project "The Unlikely Journey," which earned the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography. Her work explored how the boy once defined by war had grown into a man defined by resilience.

Now 31, Saleh lives with his family in the United States, continuing the life that began on that operating table in 2003. Fitzmaurice's recent images show a thoughtful adult, grounded and composed, still wearing his prosthetic arm as a reminder of both loss and endurance. Yet, as advanced prosthetics evolve, so does Saleh's story. In late 2025—marking 22 years since the explosion—Dr. Johannigman, leveraging his Army Reserve ties to Brooke Army Medical Center, is advocating for Saleh to receive a state-of-the-art myoelectric arm at the Center for the Intrepid in San Antonio.

"Lion Heart fought for every step then," Johannigman says. "Now, we're fighting to give him the grip to build his future."

He remains deeply connected to his roots, keeping in touch with relatives in Iraq and occasionally speaking about his experience to humanitarian groups. His story has become part of a larger dialogue about the civilian cost of conflict and the power of compassion that crosses borders. The nickname Lion Heart remains fitting. It is less about survival now and more about purpose.

The Surgeon Behind the Story

For Dr. Jay Johannigman, the "Lion Heart" case became a defining moment in a lifetime devoted to trauma medicine.

Johannigman graduated from Kenyon College in 1979 and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in 1983. After completing postdoctoral training in trauma and surgical critical care, he joined the U.S. Air Force Reserves, where he served as a trauma and critical care surgeon at Wilford Hall Medical Center in San Antonio.

By 2003, he was a lieutenant colonel and deputy commander of the 332nd Expeditionary Medical Group in Iraq. His leadership in combat trauma care during Operation Iraqi Freedom established his reputation as one of the military's foremost experts in critical care and aeromedical evacuation.

After returning home, Johannigman brought those lessons into the civilian world. He joined the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and founded the Cincinnati Center for the Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills (C-STARS), a military-civilian training partnership that has since educated thousands of surgeons, medics, and nurses in combat-style trauma care.

Over the next two decades, he would deploy eight times to Iraq and Afghanistan, serving as Trauma Director, Deputy Commander, and Director of Clinical Services for combat hospitals. His innovations in Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) and Critical Care Air Transport Teams (CCATT) reshaped modern battlefield medicine, saving lives on and off the front lines.

He has been recognized with numerous awards, including the Legion of Merit in 2022, the Bronze Star Medal, the Meritorious Service Medal, and the Military Health System Research Symposium's Distinguished Service Award.

At every stage of his career, the story of Lion Heart stayed with him. "It reminded me why we do this work," he told medical colleagues years later. "Sometimes saving one life can shift the course of many others."

Beyond the Battlefield

In 2025, Colonel (Ret.) Jay Johannigman officially retired from active military service after more than forty years of combined civilian and military practice. He returned home to Cincinnati, Ohio, the city where his academic and clinical journey began.

Today, he continues to work in trauma system development, serving as a mentor through the American College of Surgeons and consulting on emergency preparedness for hospitals across the Midwest. He has advocated for wider access to whole-blood transfusion programs, a technique refined on the battlefield and now being integrated into civilian emergency medicine, especially in rural and pre-hospital settings.

His current focus is on building bridges between war-zone medicine and public health resilience. "Cincinnati is where I learned to connect the two worlds," he told a recent audience at a trauma conference. "The tools that save soldiers should also save civilians."

He often reflects on the boy who once arrived on a stretcher at Tallil Air Base. "Lion Heart showed me that courage isn't limited by borders," he said. "Protocol saves lives, but empathy saves souls."

The Legacy

The story of Saleh Khalaf and Dr. Jay Johannigman continues to transcend generations. What began as a chance encounter in the chaos of war has become an enduring lesson in compassion and shared humanity.

Through C-STARS, Johannigman's training programs have helped shape the next generation of trauma surgeons. Many of his students now serve in combat hospitals and civilian trauma centers across the world, carrying forward principles rooted in that one defiant act in 2003 when saving a child became more important than following the rulebook.

Meanwhile, the narrative of Lion Heart has gained significant momentum. The original San Francisco Chronicle coverage inspired photo exhibits, humanitarian lectures, and ongoing discussions about medical ethics in conflict zones. Fitzmaurice's recent work ensures the world still sees the face behind those statistics—a boy who once lost everything and found hope again through human connection.

For Dr. Jay Johannigman, this connection continues to serve as his guiding principle. After decades of surgery and eight deployments, he measures success less by medals and more by impact. "It comes down to moments," he said in a recent interview. "It's the moment when someone who shouldn't have survived succeeds," when someone who was broken walks again. "That's what stays with you."

The war in Iraq has faded into history. The headlines have long since moved on. But two lives, one Iraqi and one American, remain proof that empathy, when acted upon, can ripple through decades.

Occasionally, the greatest victories in war are not measured in territory or triumphs, but in a heartbeat that keeps going long after the battlefield goes silent.

ⓒ 2026 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.